And then there is the new music...

For each 3Seasons performance, one Vivaldi season is dropped and the corresponding section of Byron Au Yong's just minted suite of the same name is substituted.

The new composition is difficult and strange to ears accustomed to Vivaldi, especially for dancers who had learned Olivier's choreography, which is so very connected to the Vivaldi score. On first hearing, the dancers found it "different," "unnerving," "jangly," "weird," "not to my taste."

The new composition is difficult and strange to ears accustomed to Vivaldi, especially for dancers who had learned Olivier's choreography, which is so very connected to the Vivaldi score. On first hearing, the dancers found it "different," "unnerving," "jangly," "weird," "not to my taste." It bothered them.

The new composition has same number of measures, the same tempos as the Vivaldi, but they said, "I can't hear it," "it doesn't make sense," "I don't recognize it."

All were game to try, though!

And in whatever season Byron's version is substituted, the lighting, like the dance, also follows patterns established for Vivaldi. As lighting designer Michael Mazzola observed, "the new music recontextualizes things in a very jarring way. It is hard."

It was hard, too, for the musicians to get in sync with the dancers.

The challenge remained considerable for all three performances, because the dancers had very little exposure to any of the new music ahead. Rehearsals with Byron's score were few and brief, and it wasn't known until shortly before a show which season would be substituted. The same challenge faced Jill Hanson, stage manager in charge of lighting cues.

The challenge remained considerable for all three performances, because the dancers had very little exposure to any of the new music ahead. Rehearsals with Byron's score were few and brief, and it wasn't known until shortly before a show which season would be substituted. The same challenge faced Jill Hanson, stage manager in charge of lighting cues. But sometimes, unexpectedly, Byron's composition took on a certain manic or sneaky, skewed relation to Vivaldi, so that in a peculiar way it fit, even elucidated the original.

On opening night (Friday), "Autumn" was danced to the new music. Because that season begins with a jaunty sextet of three women and three men, Byron's rollicking soundscape— which had an old-fashioned amusement park feel to it, with toy piano and a pronounced tune and rhythm—established a mood of cheerful, good-natured, even innocent fun.

But on Saturday "Summer" was substituted instead. In Olivier's interpretation, summer is the heaviest month. The sultry, hot atmosphere of the season (at least in some parts of the world) infected the choreography. This is the sequence that begins with Kaori (perhaps representing humanity or the earth or nature?) laboriously dragging objects attached to her by ropes across the stage...

Byron's harsh, jagged music created a grim, despairing mood, so that when Vivaldi returned in "Autumn" and the three couples flirted and cavorted, their moves now appeared artificial, cynical, soulless. And the final moments of "Winter" felt tragic. At least to me.

But why do any of this? The Vivaldi music, although so familiar one almost has trouble hearing it sometimes, is undeniably beautiful, finely crafted, full of contrasts and wonderful melody. What is the point in throwing it off balance, tossing it away?

The question brings us to the very core of 3Seasons. Surely more now than in any other time of our lives—because of global weather changes and our greater awareness of other parts of the planet with different climates—we experience the seasons as much less predictable or automatically comprehensible/stereotypical than they used to be.

The point, Olivier's central idea with this piece, and Byron's too, is to take us, through the dancers, beyond our comfort zone, beyond the beautiful music we have grown up with and become overly accustomed to. In this era, because of its incredible electronic connections, there is virtually no such thing as isolation any more, even if we wish for it. We can't help but be impinged on by catastrophes like Haiti's earthquake—or styles halfway across the globe.

The point, Olivier's central idea with this piece, and Byron's too, is to take us, through the dancers, beyond our comfort zone, beyond the beautiful music we have grown up with and become overly accustomed to. In this era, because of its incredible electronic connections, there is virtually no such thing as isolation any more, even if we wish for it. We can't help but be impinged on by catastrophes like Haiti's earthquake—or styles halfway across the globe.  In fiction these days, there is a suspicion of any story that has too happy an ending. The same is often true in other arts. In a certain odd way, I think, by introducing at the outset the knowledge that the known is going to be disrupted, Olivier somehow gives us permission to enjoy the elegant and ordered music.

In fiction these days, there is a suspicion of any story that has too happy an ending. The same is often true in other arts. In a certain odd way, I think, by introducing at the outset the knowledge that the known is going to be disrupted, Olivier somehow gives us permission to enjoy the elegant and ordered music. Not that he has, by any means, made merely pretty dances. A great deal of this work is enigmatic, harsh, off-kilter. By suiting it so perfectly to the Vivaldi score, harsh themes are rendered comprehensible, in a way even beautiful. But if you add to that another layer of uncertainty, a musical landscape with the same temporal shape but an altogether different feel, everyone—the viewer, like everyone involved in making the performance—has to start again from scratch, an exercise that might make us delight in returning to the original Vivaldi or thrill to an unexpected, realigning jolt.

As for the dancers, the new music affected their relations in performance. I overheard one (Jonathan?) speak of hearing the footfalls of another entering behind him, and using that as his cue.

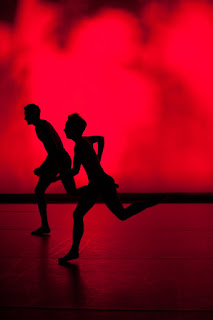

Ty said, "we look to each other more, listen to the flow of breathing." Several mentioned how they needed to pay more than usual attention. One remarked that "we have to depend on each other." For lack of the usual aural prompts, the dancers have to reconnect, in new ways, with each other, with the live music, with the audience.

Perhaps we, as viewers, have to do the same...

Ty said, "we look to each other more, listen to the flow of breathing." Several mentioned how they needed to pay more than usual attention. One remarked that "we have to depend on each other." For lack of the usual aural prompts, the dancers have to reconnect, in new ways, with each other, with the live music, with the audience.

Perhaps we, as viewers, have to do the same...